I think cybersecurity practitioners should be able to program. If they do, they can understand computer technologies better and they can automate tasks by building tools. This is something I want to demonstrate a bit in this post and the next one.

NOTE: You can read this post also on github.

But why Go

I think no one really doubts it’s a good thing to be able to program. But why Go and not some other language, like Python? I think you should also learn Python and Bash and Javascript, if you can. Following are some qualities of Go I like.

Simplicity. Hoare said that “There are two ways of constructing a software design: One way is to make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies and the other way is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies.” Go language and (many) Go programs follow this idea. You want simplicity because there’s already enough technological (and organizational) complexity. Simpler systems are easier to understand and thus tend to have fewer bugs and are easier to modify.

Security. Go is a relatively new language (version 1.0 was released in 2012) built with safety and security in mind. This is not true of languages created in the pre-Internet era that was more innocent (Python appeared in 1991).

Stability. Go maintainers intend not to break Go compatibility so you don’t need to worry that the programs you write will stop working. I also think that Go has a future because it was created and is maintained by very experienced and skilled people (like Rob Pike, Ken Thompson and Russ Cox). It’s an open source language, supported by Google and used by many other big companies, like Cloudflare or PayPal. A lot of important open source software is written in Go, for example Kubernetes or Terraform. It has a first class support on all cloud providers and most of the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) projects are written in Go.

Typed, cross-compiled to a single binary. If you are (as I used to be) familiar only with dynamic scripting languages like Python or Perl, Go will help you to really understand what are the large-scale systems languages like. What is cool is that you can build your program to run on any supported computer (CPU) architecture and operating system. For example, if you are on a Mac and want to run your tool on a Linux based Raspberry Pi:

$ GOOS=linux GOARCH=arm64 go build mytool.go

$ scp ./mytool user@raspberry.net:

$ ssh user@raspberry.net ./mytoolTo list all supported platforms:

$ go tool dist listTLS version

Imagine you (or your boss :-) read somewhere that TLS 1.2 is not fast and secure enough. Everyone should be using TLS 1.3! Are we?

Let’s have look. As usual we need two generic steps to solve this puzzle. First of all we need to know what TLS is. Second of all we check what versions are we using for our services.

What is TLS - learning by reading

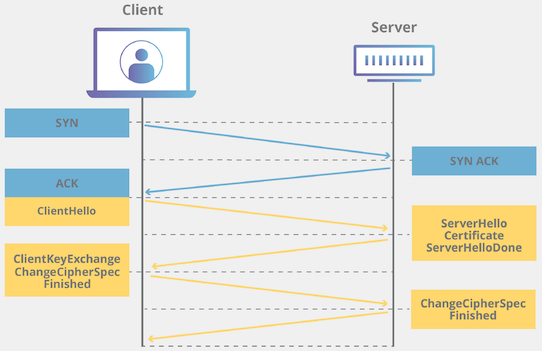

TLS (Transport Layer Security), formerly known as SSL, is a protocol to encrypt, authenticate and check the integrity of data that is transferred over network. You can think of it as secure TCP. The nowadays omnipresent HTTPS is an extension of HTTP that uses TLS underneath. As you can see in the picture below in yellow, a TLS connection is initiated via TLS handshake. (The blue stuff is the standard three-way TCP handshake).

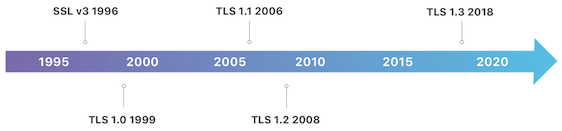

One of the things negotiated during the handshake between the client and the server is the version of TLS to use. There are several TLS versions. TLS 1.3 is the latest version, that also happens to be the fastest and most secure. You should be using TLS 1.3.

What is TLS - learning by doing

There’s a difference between knowing the path and walking the path. Or, as Evi Nemeth said: “You don’t really understand something until you’ve implemented it”.

TCP

Let’s start with TCP because we said that TLS is kind of a secure version of TCP. All we need to implement a TCP server and client is inside the net standard library package.

The server code has three parts: listening, accepting and handling.

First we need to start listening for incoming TCP connections on some address (host:port):

ln, err := net.Listen("tcp", "localhost:8000")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer ln.Close() // execute when surrounding function (main) returnsThen we enter an infinite loop in which we accept and handle incoming connections:

for {

conn, err := ln.Accept()

if err != nil {

log.Print(err)

continue

}

go handle(conn) // handle connections concurrently

}The handle function is running in a goroutine which means the program doesn’t block waiting for the function to return. It continues running the loop handling multiple connections concurrently.

The connection handling in this case is really simple, we just copy back whatever we receive:

func handle(conn net.Conn) {

defer conn.Close()

io.Copy(conn, conn)

}The client code has also three parts: connecting, writing and reading.

First we need to connect to the address of a TCP server:

conn, err := net.Dial("tcp", "localhost:8000")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer conn.Close()Next we send out some bytes (converted from a string):

_, err = io.WriteString(conn, "Hello from client.")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("client write error: %s", err)

}And then we receive some bytes (printed as a string):

buf := make([]byte, 256)

n, err := conn.Read(buf)

if err != nil && err != io.EOF {

log.Fatal(err)

}

fmt.Printf("client read: %s\n", buf[:n])Let’s run the server and client:

$ go run tcp/server/echo.go

# from another terminal

$ go run tcp/client/main.go

client read: Hello from client.You can find the whole code here.

TLS

As we’ve learned, TLS adds encryption, authentication and integrity checking to TCP connections. Let’s see.

The server code will be very similar to TCP server

only we’ll use the tls

package instead of the net package:

ln, err := tls.Listen("tcp", "localhost:4430", config)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer ln.Close()Ok, we need some configuration for TLS to work. TLS uses public key cryptography. TLS server needs:

- a certificate that will be sent to a client to authenticate the server and encrypt the communication

- a private key to decrypt and sign data

certFile := flag.String("cert", "cert.pem", "certificate file")

keyFile := flag.String("key", "key.pem", "private key file")

flag.Parse()

cert, err := tls.LoadX509KeyPair(*certFile, *keyFile)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

config := &tls.Config{Certificates: []tls.Certificate{cert}}Let’s run the server:

$ go run tls/server/echo.go

2023/09/26 21:02:33 open cert.pem: no such file or directory

exit status 1Right. We don’t have the certificate or the private key. Let’s create them using mkcert and re-run the server:

$ mkcert localhost

<... snip ...>

$ go run tls/server/echo.go -cert localhost.pem -key localhost-key.pemX509 certificates contain server’s public key, along with its identity and a signature by a trusted authority (typically a Certificate Authority). We can have a look:

$ openssl x509 -in localhost.pem -text -nooutThe TLS client differs from the TCP client in a that it needs a trusted CA certificate that can be used to verify the server:

certFile := flag.String("cert", "cert.pem", "trusted CA certificate")

flag.Parse()

data, err := os.ReadFile(*certFile)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

certPool := x509.NewCertPool()

if ok := certPool.AppendCertsFromPEM(data); !ok {

log.Fatalf("unable to parse certificate from %s", *certFile)

}

config := &tls.Config{RootCAs: certPool}

conn, err := tls.Dial("tcp", "localhost:4430", config)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer conn.Close()$ go run tls/client/main.go -cert localhost.pem

client read: hello from clientYou can find the whole code here.

No comments:

Post a Comment